A sketch of the village by John Warner Barber (1835) shows the buildings used by the Foreign Mission School, to the right of the church at center.

Today I am delighted to have a guest blogger. My friend, Betty Jamerson Reed has agreed to share her article regarding a piece of history about which I knew nothing! I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Love Blooms, School Dies

by Betty Jamerson Reed

It was a great idea! Instead of building schools or seminaries in the far reaches of the uncivilized world, leaders of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions decided to establish a seminary in Cornwall, Connecticut, and educate talented youth from overseas as well as gifted young Native Americans. After completing their course work, those students would return home to serve as preachers, evangelists, businessmen, teachers, and health care workers. The Foreign Mission School would pave the way for its students to experience the civilized world and gain knowledge of other regions by interacting with their classmates.

The school opened in 1817, and students from Hawaii, India, East Asia, and the Indonesian islands began to assemble there. Initially, the seminary was flourishing, but soon its existence was challenged by romance. Love became an issue as the foreign

youngsters and local White girls became attracted to one another and pondered interracial marriages.

Indeed, love had crossed the racial boundary for centuries. French fur traders frequently established homes with Native American wives. The father of the well-known Sequoyah (c. 1770-1843), developer of the Cherokee syllabary, was a White man who served in the Virginia militia. No matter how often such interracial marriages may have taken place, when two Cherokee students at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall (1817-1827), Connecticut, announced their intentions to marry local White girls, hostility reared its ugly head.

In the early 1800s, Cornwall’s residents loathed the idea that any White woman would agree to become the wife of a Native American. But that possibility turned into an intense local issue, one that the community opposed in loud and near-lethal public battles.

Two Cherokee students, who were close relatives, fell in love with the daughters of prominent community members, and the girls they wooed accepted their marriage proposals. One of the cousins eventually became a successful businessman, an essential member of the Tribal Council, a frequent representative of his Nation in Washington, and an attorney. He was the handsome John Ridge. The other was Elias Boudinot, a writer who edited the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper in the United States. Like his cousin, Elias eventually became caught up in tribal politics.

John had suffered frequent bouts of illness since early childhood. Moving to Connecticut with its harsh cold triggered his frailty. He became ill, and his doctor ordered complete bed rest. As time passed and his health did not improve, the school steward, John P. Northrup, invited the ailing youth to move into his family home until he grew strong enough to return to classes.

There Northrup’s 14-year-old daughter carried meals to the 18-year-old John. As the auburn-haired, blue-eyed Sally (Sarah) and the handsome youth spent time in one another’s company, they fell in love (Starkey, 1973). Before long, the couple decided to marry.

Soon they revealed their intentions to Sally’s parents. Learning of their daughter’s wish to wed the Cherokee youth stunned the Northrups. Immediately they took action to end the romance. They sent Sally away to live with her grandparents and strongly urged them to

introduce her to young white men, but that ploy failed. Being separated from the man she loved depressed Sally, and she lost her appetite, refused to eat, and became ill. Her grandparents became concerned about their granddaughter’s illness and sent her back home. There she soon learned that her suitor faced the same dilemma.

John had also failed to gain his parents’ blessing for their marriage. In addition to Sally’s being white, their refusal stemmed from the matrilinear practice of the Cherokee Nation; Cherokee children became citizens by way of their mother’s lineage. Marriage to a white woman would rob John’s offspring of their Cherokee heritage (Starkey, 1973).

But John refused to give up. He persisted in begging for approval to marry Sally. Finally, his mother gave John the hoped-for permission, but the Northrups held firm, refusing to sanction their daughter’s marriage to a Cherokee.

Sally’s response was just as strong. She continued to plead with her parents to allow her to become John’s wife. At last, the Northrups offered a compromise: If Sally agreed to postpone the marriage for two years and if John’s health improved, they would allow the wedding to take place Elated, the couple agreed to the arrangement (Ehle, 1988, 164).

After two years passed, the couple continued to profess their love for one another and their desire to become husband and wife. With permission from each set of parents, the couple announced their wedding plans. At once, the Connecticut community proclaimed its horror at such a marriage. Local journalists ridiculed Sally’s willingness to become a “squaw” by marrying a “savage.” Public outrage permeated the town. The community forbade any such union and resorted to terror tactics, but such hostility did not halt the marriage.

The couple became husband and wife in a wedding held at the Northrup home on January 27, 1824. The town’s citizens ordered the couple to leave their village. At once, John took his bride far away to the Cherokee Nation, where Sally received a warm welcome. Eventually, the Cherokee leaders changed their laws allowing John to assume an active role in the tribal council.

But romance also blossomed for his cousin, Elias Boudinot. Another scandal occurred when that young man fell in love with a White girl. It happened this way: Colonel Benjamin Gold, a prominent citizen well-known throughout Connecticut, supported the Foreign Mission School and entertained its students in his home. There Elias met the Colonel’s daughter Harriet, and the two formed a friendship. Elias became ill and returned to his home without graduating, but he and Harriet corresponded. In the beginning, she was simply concerned about her friend’s health, but their letters became filled with an exchange of interests and opinions. They shared a great deal in common, despite their racial backgrounds. As time passed, the couple professed their love for one another, and Elias proposed in one of his letters. Harriet accepted. Then she shared her intention to marry the brilliant Cherokee with her parents.

From the very moment Colonel Gold learned that his daughter wanted to become Elias’s wife, he ordered her to put any thought of marrying that Cherokee out of her mind. Horrified, the young woman lost her appetite, refused to eat, and became visibly depressed. Heartbroken, Harriet projected an aura of sadness and grief. She was heartbroken.

Her condition worried her parents and caused them great anxiety. Alarmed about Harriet’s health, the Golds agreed, though reluctantly, to the couple’s marriage. Once their wedding plans became public knowledge, rage tore through the community with rocket speed. White men bombarded Elias with letters threatening to lynch him if he showed his face in Cornwall. They ordered him to stay away or face dire consequences. Despite all this furor, the brave Elias returned to marry his betrothed.

His arrival heightened public resentment. Anti-Cherokee sentiment highlighted newspaper editorials. Cornwall residents tarred and feathered figures representing the young lovers. Local townspeople burned the couple in effigy on the village green, with Harriet’s brother, Stephen, lighting the pyre.

Unwilling to deny their daughter’s happiness, the Golds continued with plans for her wedding. The couple exchanged marriage vows on March 28, 1826. Due to continuing intimidation, the couple was surrounded by guards, even on their wedding night. The next day Elias left for home with his bride (Starkey, 1973, 73). Later, Harriet wrote “I remember the . . . thorny path I had to tread . . . but . . . a kind affectionate devoted Husband . . . with other blessings, have made amends for all.” (cornwallhistoricalsociety.org).

Despite the outcry brought on by their love affairs, each couple enjoyed a happy marriage, though each ended in tragedy. Becoming the wife of a rich and powerful man opened the door to an exciting lifestyle for each woman.

Sally and Harriett also found pleasure in the companionship of White missionary couples and teachers. With the onset of motherhood, the two women became actively involved in their children’s education. Sally invited educator Sophia Sawyer to set up a classroom in her home to instruct local children. There Harriet often taught music and performed for the students (Carter, 1976). Each woman relished her life in the Cherokee Nation.

But tragedy ended the Boudinot marriage. On August 14, 1836, Harriet died due to complications from childbirth. Though devastated, Elias had his children to think of, and, in the spring of 1837, he married Delight Sargent, a white missionary teacher.

But trouble crushed the lifestyle enjoyed among the Cherokees. Peace in their Nation ended because greed and politics spawned ill will. The discovery of gold on tribal land stirred the envy of their white neighbors. It caused the leaders in Washington to investigate the possibility of moving the Cherokee Nation to land in the West. The citizens of Georgia demanded ownership of Cherokee property, and Andrew Jackson, with the support of other politicians, gained the congressional endorsement of an act to remove the Cherokee nation. Ensuing greed led to the state’s sponsoring a lottery of tribal property, which allowed citizens of Georgia to gain possession of homes, orchards, farms, and all other Cherokee possessions.

The debate about the Removal of the Cherokee Nation to territory in the West continued, but, finally, all the political haggling in Washington ended with the signing of the Treaty of New Echota, which compelled the Cherokee Nation to exchange their long-held tribal lands for territory in the West. Those Cherokees who voluntarily signed the treaty were denounced for betraying their people. Two of those were John Ridge and Elias Boudinot; each man signed because he was convinced that the tribe’s removal was inevitable and pointless to continue fighting against such action. Once John and Elias had agreed to exchange their tribe’s seven million acres for five million dollars and territory in the West, their tribe members denounced them as traitors.

But the unhappy Cherokees had to postpone taking action against such seditious acts because more immediate problems demanded their attention. Their people, accompanied by a military escort, would be forced to march to their new home if they could find no other means to travel. Few Cherokee families could afford to move west without joining the march. The wealthy John Ridge, accompanied by Sally and their children, went on ahead to the Indian Territory to prepare for the arrival of their neighbors and friends. In anticipation of their arrival, John built a store, a schoolhouse, and other accommodations. He and his wife also traveled to New York and brought back supplies to be available to his tribesmen upon their arrival.

After their “march” ended, those Cherokees who had survived its rigors collapsed to rest and recuperate. But once the survivors regained their strength, they yearned for revenge against any member of their nation who had sold out their tribe by agreeing to the move westward. To do so, they invoked the traditional Cherokee “blood law,” which required vengeance. So, early on the morning of June 22, 1839, sounds of a home invasion awakened the John Ridge family. Assassins dragged John from his bed out into the yard and stabbed him multiple times. Men restrained Sally from rushing to his side, but, as he lay dying, John lifted his head and locked eyes with his wife. He started to speak, but could not express himself because blood was filling his mouth (Ehle, 1988). Their marriage ended there with Sally’s beloved husband lying dead on the ground. Frightened for the lives of her children and her own, Sally soon fled to Arkansas and lived there until pneumonia claimed her life on March 31, 1852.

On that same day–June 22, 1839− Elias Boudinot set out to check on the construction of a house he was building for his family. As he drew near the site, a man approached him, calling out that a sick family needed medicine. Since dispensing medication was one of his duties, Elias turned back to join the man and two others. He walked just ahead of them as he returned to pick up the needed medication. He took only a few steps before they attacked him.

Sounds of violence brought the carpenters and Elias’s bride, Delight, rushing to the scene. There they found the body of Elias on the ground with a knife in his back and his scalp severed by a tomahawk. His assassins had fled from the scene (Starkey, 1973). Delight knelt beside her husband, calling his name, but he could not answer. All life had left his body.

Horrified, but with concern for others in danger, Delight postponed giving in to the agony of grief to warn others who might be in trouble, such as Chief John Rolf and her brother-in-law Stan Watie (Starkey, 1973, 313). Only after sending hurried messages to potential victims did Delight allow personal heartbreak to engulf her (Starkey, 1973). A short time later she returned to New England to care for her stepchildren, who were away visiting their grandparents at the time of their father’s murder.

Back in Connecticut, love continued to challenge relations between the seminary and the community. Other romances between local girls and foreign students blossomed in Cornwall, and the Foreign Mission School, founded to educate talented young men from “heathen” worlds,

closed its doors. Its directors stated simply that it would be best for the young men to return to their homelands to receive further education and training. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions shuttered the school in 1826. Love was one major cause of its demise, proving that even great ideas can fail.

References

Carter, Samuel, III. 1976. Cherokee Sunset: A Nation Betrayed. New York: Doubleday.

Connecticut Humanities. 2022. “An Experiment in Evangelization: Cornwall’s Foreign Mission School.” Accessed February 04, 2022.

Ehle, John. 1988. Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. New York: Anchor Books.

Hendricks, Nancy. “Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge (1804–1856).” Accessed February 4, 2022. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/sarah-bird-northrup-ridge-11942.

Pate, James P. 2022. “Ridge, John.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=RI003. Accessed February 4, 2022.

Poole, Arlen D. “Life of Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge.” Flashback 57 (Summer 2007): 49–66.

https://connecticuthistory.org/an-experiment-in-evangelization-cornwalls-foreign-mission-school/ Accessed February 19, 2022.

Starkey, Marion L. 1946. The Cherokee Nation. New York: Knopf.

Used by Permission: copyright Betty Jamerson Reed 2022

To connect with Betty: http://www.bettyjamersonreed.com OR on Amazon.com—authors page and McFarland.

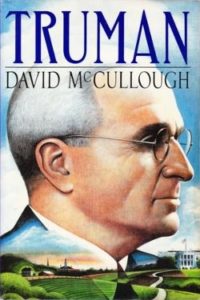

As President Harry S Truman said,

As President Harry S Truman said,

I also loved Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White. But they never said anything about training Wilbur to follow directions before the fair. Maybe if they had he would have won first place. I guess it wasn’t in the plot.

I also loved Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White. But they never said anything about training Wilbur to follow directions before the fair. Maybe if they had he would have won first place. I guess it wasn’t in the plot.

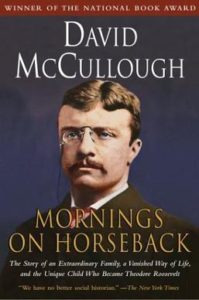

A couple of weeks ago I finished reading Mornings on Horseback, also by David McCullough. It’s not a biography, but rather the chronicling of a family, the Roosevelt family. It starts with President Theodore Roosevelt’s grandparents and parents, and then settles into a close-up-and-personal look at the family in which Teddy Roosevelt grew up. It follows them through to the point where Teddy is about to marry his second wife, then quickly ties up the loose ends, letting you know how each of his siblings’ lives went after that.

A couple of weeks ago I finished reading Mornings on Horseback, also by David McCullough. It’s not a biography, but rather the chronicling of a family, the Roosevelt family. It starts with President Theodore Roosevelt’s grandparents and parents, and then settles into a close-up-and-personal look at the family in which Teddy Roosevelt grew up. It follows them through to the point where Teddy is about to marry his second wife, then quickly ties up the loose ends, letting you know how each of his siblings’ lives went after that.